Mixing oil and water

Psychologists often find that opposites attract in couples with personality disorders.

Psychologists often find that opposites attract in couples with personality disorders.By Bridget Murray

By now, Florida psychologist Florence Kaslow, PhD, has seen the pattern so often among some couples that it's practically a clinical archetype: Both parties have personality disorders (PDs)--but on opposite ends of the spectrum.

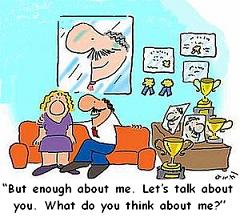

The fastidious, stoic spouse with obsessive-compulsive PD clashes with the often messy, flamboyant spouse with histrionic PD. Or, likewise, the self-absorbed, self-important person with narcissistic PD spars with the needy, clingy partner with dependent PD.

"They seem to have a fatal attraction for each other in that their personality patterns are complementary and reciprocal--which is one reason why, if they get divorced, they are likely to be attracted over and over to someone similar to their former partner," Kaslow says.

Problems derive from each partner's unexpected reaction to the other, Kaslow says. She explains: "These people often literally see the other person as 'their other half.' But that half is one they have cut off in themselves, so they're essentially attracted to the thing they've rejected or have a negative attitude toward."

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that each partner stirs up some unconscious, unresolved developmental issue in the other, says Joan Lachkar, PhD, a Los Angeles practitioner who writes on partners who exhibit certain traits and characteristics of narcissistic and borderline PDs. For example, explains Lachkar, an instructor at the Southern California Psychoanalytic Institute, the borderline's neediness chips at the narcissist's armor against intimacy, and the narcissist's rejection stokes the borderline's abandonment anxiety, reaction to shame and tendency to feel shunned or abused.

Such partners are frequently developmentally arrested, forming a pattern that Lachkar calls "the dance" in a narcissistic/borderline relationship. The dysfunction in that dance--the narcissist's emotional withdrawal and the borderline's need for rejection and emotional upheaval--can stem largely from childhood attachment problems, a hallmark of personality disorders, Lachkar argues.

In adult relationships, Solomon adds, people with PDs may act out early abuse, neglect, violence and other forms of childhood attachment failure--although, as pointed out in the literature on PD underpinnings, it's not clear how much these failures stem from parental abuse, already existing childhood pathology that elicits negative parental reactions or an interplay of both.

Causes aside, Solomon maintains that the ingrained PD mechanisms form early: "When a child is terrified at 0 to 18 months, the left brain--the rational language part of the brain--has not yet developed, so the right brain either puts up a shield or views the self as flawed," Solomon says.

Combating those right-brain reactions by adding left-brain cognitive functions is key to treating couples battling PDs, Solomon says. However, practitioners lack research on how to effectively do that, says Links, author of the article on couples' treatment prospects for people with narcissistic PDs. In that paper, Links drew on his own clinical experience to argue that, when the partnership involves a narcissist, its survival depends on that person's ability to:

* Curtail acting-out behaviors, such as using drugs or alcohol, overspending, acting in sexually compulsive ways or physically or verbally abusing a partner.

* Reduce levels of defensiveness and show vulnerability.

In addition, says Links, the Arthur Sommer Rotenberg Chair in Suicide Studies at the University of Toronto, the couple needs to "rebalance" itself so that that the narcissist's partner--likely a more masochistic, dependent type--still gratifies the narcissist's need for admiration, but also can glean increased love, approval and support from the narcissist.

Bridget Murray